Essay to accompany the exhibit Robert Rivers: Prints and Drawings. Held at the Linder Gallery, Keystone College, March 26-April 28, 2006.

This exhibition of Robert Rivers’ prints and drawings is special to me, because Rivers was my drawing teacher for several years at the University of Central Florida and his courses, the stuff of campus legend among students at the time, remain the single most formative influence upon my own art and my thinking about art ever since. It gives me great satisfaction to present this exhibit at the Linder Gallery, and to introduce Robert Rivers’ extraordinary artwork to northeast Pennsylvania.

The most memorable Rivers’ course I ever took was a summer figure drawing class, but because the art department’s budget had been exhausted by the time summer came around, there was no money to afford a model. Rivers’ solution was nothing short of inspired. For several days before the first class session, he constructed a monumental still life that spanned the forty or so feet across the drawing studio, and that contained all manner of objects: animal bones, a human skeleton, mannequins and mirrors, boxes, boards, and platforms, a pedestal table, and rolls and rolls of masking tape stretched from every corner, visually tying the entire assemblage together. The still life looked like the wreck of a ship in the middle of the studio, but somehow it was beautiful.

We, the students, were assigned neatly marked-off spaces around the perimeter of the still life, and were required to draw from those spaces for the entire term. The challenge we would face became readily apparent within the first class or two: How on earth were we going to make interesting drawings of the same subject from the same viewpoint for an entire summer? How on earth would we sustain our interest in this subject as the term progressed?

Not everyone did sustain their interest. Some dropped out; others got bored and their drawings floundered. But most of the class at least reached a threshold where their drawings had either to break through to some kind of new, creative solution or they would grow stale and redundant. For those who managed to break that barrier, they began to draw the still life in a very different way. In short, their drawings ceased to be mere depictions of the set up and became arbitrations between the true nature of the objects and the nature of each student’s truest responses.

I will never forget a classmate who wrestled so much with his drawings that the surface of the paper—a heavyweight, printmaking stock—began to erode from too many erasures. More than once, he wore clean through a drawing. But what he eventually realized was that his persistence was more than just a means to an end; it was his honest response to the world before him. His struggle to break through with his drawings was, in fact, the very thing to which he had broken through.

I mention all of this because that summer drawing course, I think, was a pretty accurate reflection of Rivers’ approach to his own art (as often is the case with the best teachers). If I am correct, it might be summarized thusly: look, understand, respond, start over and do it again and again. The great work is not something one willfully creates, but something that emerges—at its own volition—from the tireless creation of countless near misses and outright failures.

Which is not to suggest that any of these works come easily. The painter Richard Diebenkorn famously wrote that he wanted his art to be difficult to do, that the easy image (or the breezy mannerism) was the greatest dissatisfaction. Rivers would almost certainly agree. As Kevin Haran notes in his essay, examine a Rivers drawing and you will see a painstaking process, a relentless struggle to get the image right, and this is just as true of his etchings. Indeed, it is a Herculean task, and for more than just an aesthetic end; in Rivers’ work, the quest for “rightness” becomes a kind of moral necessity, a labor performed at the insistence of the gods.

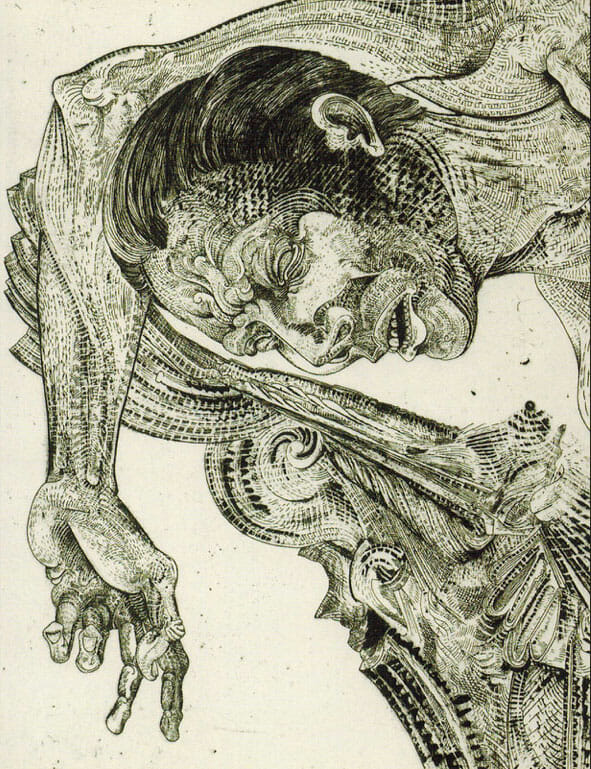

Haran also notes the contrast of imagery in Rivers’ art, and this extends to the ideas and subject matter with which the artist deals. In Amazon (fig. 1), it is the contrast of the female warrior with the resting male, identified from another print in this exhibit as the hero Hercules (Hercules at Rest). The Amazon wrestles a great snake, suggestive of the male principle and perhaps of Hercules himself, that paragon of manliness. Nearby, two heads float in the water, perhaps belonging to other Amazons.

The printmaker Henry Walton, among others, has observed of Rivers’ art a self-referential symbolism, in which the artist (either Rivers specifically or “the artist” generically) appears in different guises: a majestic horse, a blood-thirsty lion, an elephant-headed man wielding a sculptor’s mallet and chisel. In this work, the artist must be Hercules.

Readers of mythology will be reminded by this print that Hercules’ ninth labor was to steal the girdle of the Amazon queen, Hippolyta. This girdle, given to the queen by her father, Mars, was a great prize, a gift from the gods, and though not depicted in Rivers’ etching, it is significant to the meaning of the work. It is significant, I think, because it is the art itself, perhaps this individual print, or Rivers’ art in general, or just art in general. And though we cannot tell by looking at the print whether Hercules will succeed in stealing Hippolyta’s treasure (the queen and the snake seem locked in a moment of stasis that could yet go either way), we know from the myth that Hercules does complete his task, just as Rivers completed this exceptional etching.

When I look at prints such as Amazon, I am reminded, of course, of Robert Rivers and some of the things I know and remember about him, but I cannot help projecting myself and my experiences onto his metaphors. For a time, I am Hercules, stealing from the Amazon queen, and she is that giant still life Robert built in the studio twenty years ago. In this case, I’m not sure if my task was ever completed, but I’m comforted by the fact—as Robert Rivers must be—that in the end Hercules completed all his labors and was rewarded by the gods with the gift of immortality.