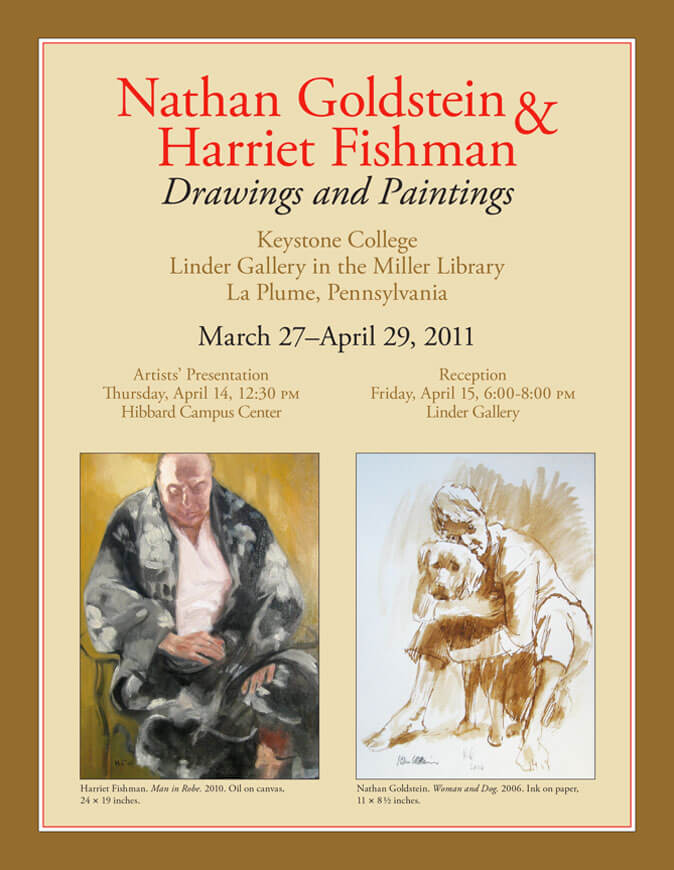

Essay to accompany the exhibit Nathan Goldstein and Harriet Fishman: Drawings and Paintings. Held at the Linder Gallery, Keystone College, March 27-April 29, 2011.

In the domain of college art instruction, Nathan Goldstein stands as a somewhat legendary figure. The author of seven textbooks on art, including some of the most widely used in college and university art courses, Goldstein’s writings on drawing, painting, and design have influenced countless art students and their professors for almost forty years.

Somewhere in the mental scrapbook of my own education, I recall Nathan Goldstein giving this advice to a group of students: “When you discover a work of art that really speaks to you,” he counseled, “ask yourself, ‘What is it that makes it so compelling?’” He continued, “When you think you have answered this question, stop…and ask yourself again, ‘What, to me, really makes this work compelling?’” He went on. “And when you think you have answered the question this time, stop again, and ask yourself, ‘Now, what is it makes this work compelling?’”

And he might have gone on still, but Goldstein had made his point: namely, that great art does not exhaust itself through a cursory experience. Rather, it unfolds its beauty and its greatness through multiple exposures, and through the deep perceptual investigations of the viewer. The trumpeter Wynton Marsalis, speaking of music, put it another way in saying, “[Art] does not come to you; you have to come to it.”

Goldstein’s pedagogical advice is a fitting summation of his practice as an artist, and of the practice of his wife, Harriet Fishman. Rooted in a rigorous traditionalism, their drawings and paintings drip with the process of looking, looking again, and even looking again. But theirs is not a mechanical rendering of visual sensations. Instead, as the title of Goldstein’s most well-known text, The Art of Responsive Drawing, attests, the works first serve the aesthetic sensibilities of the artist. In the end, the subject matter is merely a jumping off point and a coming-back-to point for an integration of representation, expression, and design.

While spousal practice in the arts is not unusual, exhibitions of both partners’ works are, and yet the juxtaposition of “his and her” artwork can be visually and psychologically intriguing. In the case of Goldstein and Fishman, the compatibility is striking. What are the similarities and what are the differences? Who influences whom, and where? If we expect the artwork to just offer us the answers, we will be disappointed. We must come to the work and really look, and really look again.