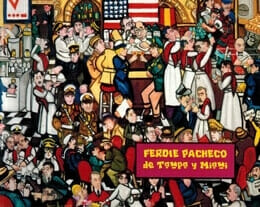

Essay from the catalog for the exhibit Ferdie Pacheco: de Tampa y Miami. Held at the Linder Gallery, Keystone College, March 29-May 1, 2005.

It is common that writings on Ferdie Pacheco describe him as a sort of modern-day Renaissance man, a jack-of-all-trades and master of many. Certainly this is true, for the Miami artist has been many things in his long and varied life: pharmacist and medical doctor, author of some fourteen books on subjects ranging from fiction to art to Spanish cuisine, two-time Emmy award winning documentarian, an internationally-recognized authority on the sport of boxing, boxing analyst and television executive, and, not least of all, a prolific and gifted painter. But what is often overlooked is Pacheco the historian, who through these varied pursuits–and especially through his writings and artwork–has chronicled the history of places and times that others might readily forget. Pacheco’s work is not just an academic history, however, as paintings rarely are and writings often only pretend to be. Rather, it is a kind of aesthetic history, researched and recalled through the interpretations of an artist. As Pacheco himself wrote in Ybor City Chronicles, “let me assure the reader that this book is not a history of Ybor City….These stories may not be the strict truth as other witnesses remember it, but they are the truth as I remember it. They are my truth.”1

The exhibition Ferdie Pacheco: de Tampa y Miami is an acknowledgment of this kind of historical truth, this aesthetic history. It focuses on two groups of paintings that have provided recurring subjects for Pacheco’s art over the last twenty years. The first of these chronicles the history of Ybor City, the Spanish, Cuban, and Italian neighborhood of Tampa where Pacheco grew up. His paintings of Ybor City capture the vibrant life of this community and its many personalities from the 1920’s through the 1940’s. The second group of paintings chronicles the plight of the Cuban community in Miami, primarily the exiles who fled there after the rise of Fidel Castro in 1958. Most of these paintings also depict the time shortly after Pacheco himself relocated to Miami, attending medical school and later running two clinics to serve the needs of the poor in the Cuban and African-American communities. Thus, the title of the exhibition refers to both the subjects of the paintings and to the artist’s own migration from one Florida city to another.

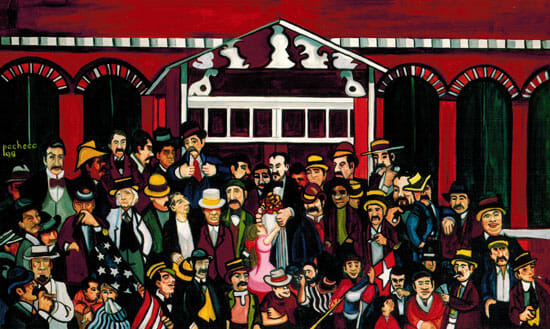

Tying the two groups together are two remarkable paintings that could belong to either group: the portrait of José Martí as a young poet, and the painting Martí in Ybor City (fig. 1).As the catalogue commentary discusses, it was Martí’s 1891 journey to Ybor City to speak to the cigar workers that established him as the leader of the Cuban Independence Movement. In turn, it is often argued that the rise of Cuba as an independent nation began, in a very real sense, in Ybor City. Therefore, these two paintings, though anachronistic, link the immigrant experience depicted in the Ybor City paintings with the later experience depicted in the Miami exilios paintings.

Perhaps the most striking aspect of these works collectively, however, is how unusual the subject matter is; that is, as a recollection of lived experiences from a bygone era. At first, it is tempting to think of Pacheco as a genre painter, a chronicler of the specific and idiosyncratic activities of common individuals. But most genre paintings depict contemporary life, the artist’s immediate experience, and Pacheco’s subjects (excepting a few portraits not in this exhibit) all reside in the past.

So is he then a history painter, a recorder of days long gone, and of the people and places who occupied those times? This also presents some difficulties, for “history paintings,” at least as academics use the term, are usually about more than just the past.2 Typically they depict grand or noble subjects, or subjects that are tragic but morally instructive. They celebrate the accomplishments of men and women whose names the viewer probably already knows, and whose deeds they might know, too. Although some of Pacheco’s works, such as a suite of U.S. Civil War paintings, meet these criteria, the works in this exhibit lack the grandeur that is typical of most history paintings (the sole exception being Martí in Ybor City). Instead, these paintings recall the experience of the common individual—or even the displaced and downtrodden—in Tampa and Miami, so much so that Pacheco has referred to his work as a kind of “people’s art.”3

Perhaps the best description of Pacheco’s art is a combination of the subjects his paintings don’t quite fit: that is, his art as “genre history.” There are precedents, to be sure. Perhaps the closest parallel is to be found in Romare Bearden’s collage-paintings of his youth in North Carolina and Harlem. We think also of Chagall’s reveries on the life of his Russian village, minus the fantastic elements; Benton’s paintings of the settling of the frontier; Rivera, Orozco, and Tamayo’s murals and paintings of the Latin American past; Faith Ringgold’s tapestries of the African-American experience; and the work of various folk artists, who have probably embraced genre history as a subject more than most trained artists have. It is no surprise that some of these artists are those whom Pacheco most admires, especially Benton and the Mexican muralists. But with the exception of Bearden, none of them so thoroughly and rigorously chronicled the life of a specific time and place as Pacheco has done–not once, but with both groups of paintings in this exhibition.

• • •

Ferdie Pacheco did not begin to paint regularly until the 1980’s, after a highly successful career running two charity clinics in Miami and, most famously, as the personal physician and fight doctor for Muhammad Ali. Born in Ybor City in 1927, Pacheco developed an early love for art. He has written of how art was a way out of the chores and labors of childhood. “My mother’s side of the family esteemed creativity above all else, so everything else might fall by the wayside when an art project had to be completed.”4 This esteem seems to have been passed down by his grandfather, Gustavo Jimenez, who was the Spanish consul in Ybor City and who introduced the young Ferdie to the art of the old masters. Pacheco recalls that of these artists, he was most drawn to the work of Daumier, and especially to the French master’s scathing political cartoons.

This love of cartooning would remain with Pacheco throughout his life. The artist grew up during the golden age of American cartooning, and the influence of cartoons on him and other painters of his generation, notably Wayne Thiebaud and Philip Guston, was profound. Pacheco was especially drawn to the cartoons in publications such as Colliers, The Saturday Evening Post, and The New Yorker, and this influence is evident in many of his paintings, in addition to the more outright influence seen in his drawings for Ybor City Chronicles (fig. 2) and in his illustrations for two children’s books.5

In 1949, Pacheco entered pharmacy school at the University of Florida in Gainesville. While at U of F, he became a frequent visitor to the university’s art department, perhaps the finest in the state at that time. There he met Fletcher Martin, the self-taught American painter and muralist who was serving as artist-in-residence. Martin became a mentor of sorts, in spite of the fact that Pacheco remained a pharmacy student. Martin also introduced Pacheco to the paintings of Thomas Hart Benton, then the most famous living American painter. In both Martin and Benton, Pacheco found artists whose work navigated freely between humor and humanity, cartoonish mannerisms and high art. And though he has not written of this as an influence, Pacheco may also have been drawn to Benton’s—and to a lesser degree, Martin’s—interest in subjects of regional, historical appeal, the same kind of “genre history” he would later paint as well.

Before that time would come, however, Pacheco would go on to earn a medical degree from the University of Miami and to begin his medical practice. He opened his first clinic in the Overtown section of Miami to serve the African-American community. In 1960, in response to the sudden tide of Cuban immigrants who were leaving their homeland following the rise of the Castro regime, Pacheco opened a second clinic on Calle Ocho (SW 8th St.) in the Little Havana section of the city. That clinic would later burn down in the MacDuffie race riots of 1980.

Shortly after the establishment of his two clinics, Dr. Pacheco’s involvement with professional boxing began. His acquaintance with the Dundee brothers–boxing promoter Chris and trainer Angelo–coupled with the fact that he ran clinics willing to serve both black and Hispanic boxers in the segregated South, led to Pacheco becoming the doctor of choice for many boxers ascending though the ranks. In 1963, he began his association with Cassius Clay, later Muhammad Ali, becoming Ali’s corner doctor and personal physician throughout the heyday of the world-champion boxer’s career. Their relationship would last until 1977 when Ali, against Pacheco’s medical advice and despite increasing damage to his health, chose to continue fighting.6 Pacheco parted with Ali and directed his energy toward his clinics, which he had continued to run throughout his “boxing career.”7

The fifteen-year association with Ali did influence Pacheco’s artistic development, largely through the many opportunities for travel and the consequent occasions to view the art of the great museums of the world. “My art education,” he wrote, “became truly extensive. I would go to Diego Rivera’s house and museum and return to paint my impressions of what I had seen….I taught myself art by copying the actual paintings I loved.”8

Finally, after closing his medical practice on Calle Ocho and losing the clinic in Overtown, Pacheco began to paint more regularly, quickly developing the bold and colorful style that would characterize his art. His distinctive subject matter emerged just as quickly. The first Ybor City paintings began in the mid-1980’s, with the subject reaching maturity over the next decade. The series continues to the present day. The evolution of these paintings coincided with Pacheco’s literary explorations into his own past and the history of Ybor City, as recorded in Ybor City Chronicles (1994) and The Columbia Restaurant Spanish Cookbook (1995). The paintings themselves were published with a narrative by Ferdie Pacheco in Pacheco’s Art of Ybor City (1997).

The Cuban exiles paintings followed, beginning in earnest in 1998. Many of these, too, were subsequently published, in Pacheco’s Art of the Cubans in Exile (2000). It is notable, I think, that in spite of the context to which the paintings relate, almost all of them are optimistic and life-affirming. Certainly the Cuban exodus was not always so, but Pacheco’s interpretation of these events is indicative of the artist’s own optimism, and of a quality that he associates with the Latin character, in general.

That Pacheco turned to painting later in life explains many of his views about art. “The artist is a distillation of all he has lived, been taught, seen, and all that has affected him in his lifetime.”9 Though undeniable, it is the kind of statement that only an artist with a great life to draw on could say without risking self-condemnation. And while Pacheco the artist may be a distillation of his life and experiences, his paintings are not a distillation but rather an amplification of that same life.

Ferdie Pacheco has written of “serendipity, that element so important in my life…”10 It is fitting, therefore, that his paintings and books—his “genre history” of the Latin immigrant experience—have coincided with, and in many cases anticipated, the recent surge of interest in Latin American culture in the arts. This interest has been most noticeable, perhaps, in popular music over the last ten years, but has also been felt in the resurgence of traditional Cuban music, and in Hispanic-influenced motion pictures, literature, and theatre. The 1999 release of the documentary film and CD Buena Vista Social Club introduced mambo, danzón, and other Cuban musical styles to a wide audience, spawning numerous spin-off CD’s. More recently, the 2003 Pulitzer Prize for Drama was awarded to Nilo Cruz for Anna in the Tropics, a play set in a cigar factory in Ybor City in 1929. These and other examples join Dr. Pacheco’s own art in establishing an aesthetic history for a people and an era. It may not always be a true and authentic history, but it is a history we are better, in the present, for having.

Notes

- Ferdie Pacheco, Ybor City Chronicles (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1994), ix.

- For a useful discussion of history painting, see Vernon Hyde Minor, Art History’s History 2d ed. (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2001), 60-65.

- Ferdie Pacheco, Pacheco’s Art of Ybor City (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1997), xviii.

- Ibid., xv.

- The children’s books are Trolley Kat Travels (Tampa: Hillsboro Printing, 2001) and The Trolley Kat Alphabet (Tampa: Hillsboro Printing, 2001).

- Correspondence with Ferdie Pacheco, January 20, 2005. Pacheco’s concern for Ali’s health led him to resign after Ali fought Ernie Shavers in 1977. He had written letters to Ali’s manager, his wife, and Angelo Dundee expressing his concerns and told Ali that he could not be responsible for what would happen if Ali continued fighting.

- In an e-mail on January 20, 2005, Luisita Sevilla Pacheco noted that, in addition to personally running his clinics during his involvement with professional boxing, Ferdie Pacheco never charged any fighter for his services. In providing medical attention to twelve champion fighters–including Ali–Pacheco’s work was entirely gratis.

- Pacheco, Art of Ybor City, xviii..

- Ibid., xix.

- Ibid., xviii.