Essay to accompany the exhibit 3 Pent Ayisyen (Three Haitian Painters). Held at the Linder Gallery, Keystone College, September 18-October 21, 2011.

When I meet with students who are considering or questioning a college degree in art, I sometimes counsel that the best reason for choosing such a major is, quite simply, because nothing else makes sense. That is, the student should major in art because the compulsion to create art overshadows any motivation to pursue other, potentially more lucrative fields. For it is the nature of true artists that they will create their work not because of social or economic incentives, but in spite of these limitations.

Indeed, the committed artist will find a way to make art even when the challenges become overwhelming. Van Gogh, to take one famous example, sold only one painting during his lifetime, a commercial disaster by any measure. Lacking the income to buy paints and brushes, van Gogh traded his paintings for supplies–in order to create more unsellable art. A profitless business model to b sure, but van Gogh reaped his profits in other ways.

However, struggling artists struggle even more in daunting times and places, where even trading one’s artwork for commercial supplies might not be an option. In present-day Haiti (that most challenged of Western nations), for example, it is wholly inspiring to see artists producing such abundant art, knowing the efforts that are needed to make such artwork possible.

In Haitian art, struggle is more than just a part of the process, however. It is often a part of the subject matter, too, for Haitian art is deeply rooted in the heritage of the people. The painters Michelet Calice (Najee), Henry Robert Derazin, and Augustin Mona are three artists whose work reflects this spirit of struggle and perseverance. And this heritage is not just from the distant past. Recent history–notably, the horrific earthquake of 2010–figures in all three artists’ work.

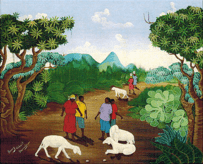

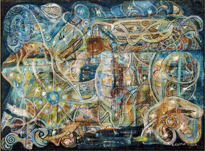

As a counterpoint to this struggle, however, there is in many paintings a spirit of great joy and optimism, and this, too, is a part of the Haitian heritage. Najee’s Family Enjoying (2010; fig. 1) conveys this joie de vivre with all the radiance of an early Matisse. Likewise, Henry Robert Derazin’s Sheep (2010; fig. 2) depicts a paradisiacal landscape, as much a scene from Haiti as one, perhaps, from the African past to which all Haitians are rooted. And Augustin Mona’s House of the Wise (2011; fig. 3) offers a nonobjective variant to the other artists’ work, a dark, colorful abstraction evoking a place (or a state of mind?) that is rich, warm, and wonderful.

Through their paintings, each of these artists explores the contradictions of hope and despair, joy and despondency, that characterize the history of Haiti. That these paintings were even realized is no small achievement; that they might also inform those of us with such privileged lives is a triumph.