Paper published in the Conference Proceedings of the 12th Annual Hawaii International Conference on Arts and Humanities. 2014. (ISSN# 1541-5899).

Though course requirements, objectives, and instructional methods in drawing vary widely among college art programs, most fine arts foundation courses are rooted in what is commonly called observational drawing or drawing from “nature.” The goal of such instruction is to train students to observe objects in the real world and to translate their perceptions into two-dimensional images using common drawing media and techniques. Typically, the student is expected to render these drawings in a manner that is visually faithful to the appearance of the real thing, with some programs or instructors emphasizing certain stylistic idioms (such as “classical drawing”) to a greater or lesser degree.

The skills of observational drawing date back to the 14th and 15th centuries, though they were most widely disseminated between the 17th through the 19th centuries in the academies and ateliers of Europe and America. In the last century, educators such as Kimon Nicolaïdes1, Bernard Chaet2, Nathan Goldstein3, and Betty Edwards4, among others, wrote popular drawing books and textbooks based on observational training, and their approaches still influence foundations drawing instruction today. Indeed, even with the influence of modern and post-modern aesthetics, and in the midst of contemporary practices in making art, college art programs widely consider observational drawing to be a fundamental component of training in the fine arts.

Certainly there are variations on what defines observational drawing. Interpretive or expressive drawing, in which students draw from arranged objects or posed models but are not expected to faithfully reproduce their appearance, is not unheard of in foundations programs, and is common in intermediate and advanced drawing courses. Likewise, using photographic references as a source—a kind of observational drawing based on translating one flat image into another—is sometimes taught as a supplement to drawing from the three-dimensional world. This is also true of the traditional practice of copying from other artists’ drawings or paintings. But all of these variations have a basis in some kind of directly observable reference, and one that students may return to in order to verify their drawings.

A counterpoint to observational drawing in any form, however, is what is sometimes called inventive drawing, envisioned drawing, or simply drawing from memory or the imagination. Though inventive drawing (and painting) is more common in advanced fine arts courses and in certain commercial art concentrations such as animation, game design, and illustration, it is often neglected or absent entirely from fine arts foundations drawing courses. For brevity’s sake, I will refer to such courses simply as foundation courses or foundations drawing courses.

Why Foundation Courses Neglect Inventive Drawing—Some Hypotheses

Though it is not the purpose of this paper to determine the reasons foundations drawing courses neglect inventive drawing, I will offer a few anecdotal hypotheses. First, by lacking a source for visual reference, inventive drawing typically results in weaker representational drawings than those that students create from observation, especially in the early years of training. To the extent that foundations drawing courses are typically focused on the students’ attainment of representational skills, inventive drawings may suggest poor student learning or poor instruction. This is especially true if the process behind an assignment is not outwardly evident—inventive drawings may be misinterpreted as weak observational drawings. This is particularly problematic for instructors when the person misinterpreting the work is an academic superior.

Second, for similar reasons of difficulty, inventive drawing poses a challenge for drawing instructors. Faculty members who are not trained in inventive drawing may be incapable of teaching these skills, or reluctant to do so if pedagogical methods require class demonstrations or correction of students’ drawings. This is less true with regard to the topic of linear perspective, the one subject that is most often taught through inventive drawing assignments. But instructional challenges are especially evident when inventive drawing focuses on complex subjects such as the human figure.

Third, inventive drawing is often associated with commercial drawing practices, particularly for comic book illustration, animation, and the like, and fine arts instruction may be biased against (or simply ignorant of) such practices. Foundations drawing courses are probably more likely to be taught by someone with a fine arts background than one in illustration, or to be supervised by a “foundations coordinator” with a fine arts background. Though the barriers between illustration and fine arts drawing and painting have been blurred in recent decades, and though many art programs require the same basic drawing courses of fine arts majors as of commercial art majors, foundations courses usually adhere to a fine arts tradition, and this tradition leans toward drawing from observation. Likewise, fine arts instructors are often watchful against formulaic or stylized approaches to drawing, and may associate inventive drawing—or illustrative practices in general—with such methods. Consequently, inventive drawing instruction may be frowned upon or misunderstood by faculty members who teach these courses.

Personal Experience

For myself, the advantages of including inventive drawing instruction in foundations courses required a certain conversion of my aesthetic and pedagogical biases. My own training as an artist was based almost exclusively on observational drawing, even through very advanced courses. Upon embarking on an academic career, I did what most young faculty members do: I began to teach as I’d been taught. As a consequence, inventive assignments were almost unheard of in my drawing and painting courses.

A few years into my career, however, I began to notice a curious and recurrent situation. For several years I was assigned to teach basic drawing in the fall semester, followed in the spring by the ubiquitous foundations course in three-dimensional design (outside my niche, but not outside my teaching assignment at the time). Usually I would have many of the same students in design as I had had the previous semester in drawing. What caught my attention was when I asked these students in design to draw out their ideas for certain projects (prior to constructing them in paper, wood, or some other unforgiving medium), their drawings were often very flawed and incomprehensible representations. Not infrequently, such drawings came from students I knew were very capable of drawing accurately from observation, since I had taught them the previous term. But when faced with drawing from an image they perceived only in their mind’s eye, they struggled to convincingly draw anything more complex than a cube.

Out of necessity, I found myself teaching inventive drawing in my three-dimensional design course, and in time, a few assignments worked their way into my drawing courses. These assignments always focused on some kind of envisioned still life or architectural form as a subject, though they variously involved problems ranging from drawing objects accurately in perspective, to correctly scaling objects in space, to shading objects as they would appear under an envisioned light source. Currently, I teach both a basic and intermediate drawing course (neither of which includes drawing from the figure) with about a 40% emphasis on inventive drawing assignments.

About six years ago, I was granted the opportunity to develop an intermediate figure drawing course with a focus on anatomy for artists. Realizing that devoting the entire semester to anatomy was not necessary for this course, I wrote the curriculum to include a significant component on inventive figure drawing. For this course, the inventive instruction also constitutes about 40% of the curriculum.

The Need for Teaching Inventive Drawing in Foundations Courses

My realization of how poorly students draw from the imagination—in spite of having learned to draw from observation—brought with it another realization: teaching students to draw inventively serves the practical, long-term artistic needs of more students than solely teaching them to draw from observation. In almost every college art program, foundations drawing courses are not just for students who choose to major or otherwise concentrate in drawing, painting, or printmaking (the traditional “drawing-centric” art forms). In most basic drawing courses, it is just as likely that any student will go on to study sculpture, ceramics, photography, graphic design, new media, or any other studio concentration that art program offers. Yet college art programs typically require of all students at least one and sometimes several drawing courses because of the belief that drawing teaches students the rudiments of visual receptivity. Learning to draw entails a kind of “learning to see,” and seeing, of course, is the basis for all of the visual arts. Thus, a student who learns something of drawing will be more responsive to visual stimuli in general, whether they are looking through the viewfinder of a camera, responding to the form of a clay vessel, or creating an image in pixels.

Certainly there is much truth in this idea, though whether such visual receptivity need be taught through drawing or whether it might be achieved through, say, a basic photo course, is arguable. In any case, beyond the somewhat vague notion of “eye-training,” the ways that drawing is useful—in a practical sense—to the professional needs of a non-draftsperson/painter/printmaker are not necessarily observational ways. The students enrolled in my three-dimensional design course needed to use drawing in a very practical way to work out their ideas for a project in another medium, not unlike how a practicing sculptor, ceramist, or designer might use drawing. But using drawing to this end requires working from an envisioned image, not drawing from something one observes.

Consequently, I have come to believe that teaching students to draw inventively is an objective that broadly serves the practical, long-term needs of more students enrolled in my foundations drawing courses than does drawing from observation. I suspect this is true of foundations drawing courses in many college art programs.

Another reason why more inventive drawing instruction is needed in foundations drawing courses is because, I believe, inventive drawing accelerates the attainment of observational drawing skills, and vice versa. My evidence for this is largely anecdotal, but I think my observations will be congruent with the experiences of many people who have taught drawing to college students for any length of time.

To explain, I first need to discuss observational drawing a bit more. Observational drawing instruction asserts the idea of looking closely at one’s subject so as to portray it accurately, and to avoid the so-called “left-brained” stereotypes or preconceived images that infect poor drawings. To this end, observational instruction emphasizes techniques such as visually measuring the proportions of an object, judging angles in relation to a horizontal or vertical standard, seeing three-dimensional forms as flat shapes, becoming aware of negative shapes, and similar approaches to seeing more objectively. Likewise, it often trains students to look closely at nature through exercises such as Nicolaïdes’ “blind contour drawing,”5 in which students draw while looking exclusively at the object before them, or “negative space drawing,” in which the student draws only the negative spaces around or within an object.

These are all very valid and useful approaches to teaching observational drawing, and learning to bypass one’s preconceived notions of what certain things look like is necessary in order to create naturalistic drawings. Indeed, many people can learn to draw reasonably well if they are trained only in this manner, provided they have something to observe when they draw. But the fact of the matter is, no drawing is an objective record of the things it portrays, and all drawings are created through the filter of an individual’s temperament and preconceptions about the things he or she examines. This is, in part, why artists have distinctive styles. It is also the reason why, when giving a group of students the same drawing assignment with the same expectations, the drawings will vary greatly in appearance, though many or all of them may be equally successful.

If the observational drawing techniques mentioned previously are a way of bypassing or suppressing one’s preconceptions, then inventive drawing, I believe, is a way of confronting these stereotypes head on. I will use the subject of the human eye as an example. In beginners’ portrait drawings, the eye is one of the most egregiously stereotyped parts of the face and head. Typically, the image that beginning students draw for an eye is something that is shaped like a football, usually too wide-open, and with lashes that radiate like the petals of a van Gogh sunflower (fig. 1).

A strictly observational approach to correcting these deficiencies might lie in having the student examine their own eye in the mirror (much less discomforting than looking closely into the eye of a model) and draw it repeatedly, perhaps limiting the drawings to contour line at first. Specific techniques might involve blind contour drawing of the eye, focusing attention on the negative shapes in the eye rather than on the more easily stereotyped positive shapes, comparing the height of the eye to its width and to other distances around it, and so forth. In time and with practice, the student’s drawings of the eye might well start to look like the real thing.

Conversely, an approach to teaching students how to draw the eye from the imagination would deal directly with the very characteristics that appear in stereotypical drawings of eyes. Such an approach would involve instruction on why these characteristics are not wholly accurate and how the student can improve upon them, probably in conjunction with a demonstration of drawing an eye step by step. The instructor would identify and name certain features of the eye, such as the “waterline,” the thickness of the lower lid that often catches the light. By identifying and naming visually important features, the features become part of the students’ conscious experience, and therefore something they are more likely to notice and ascribe significance to when drawing from observation.

Such an approach is typified—sometimes in an overly simplistic way—in books on drawing of the “how to” variety (fig. 2).

A criticism of this approach is that in teaching students to draw a generic eye, an instructor is, in effect, simply providing them with a new stereotype (albeit a better one) to replace the old one. Students taught this way will not see the distinctive appearance of a specific person’s eyes, but will merely draw the formula for “eye” that they have learned. Certainly this is a legitimate concern, and I frequently observe such formulaic drawing in my classes. Indeed, more than one student has come through my drawing courses under the influence of Manga illustration, for instance, repeatedly drawing Manga-style eyes (among other body parts) on portraits and self-portraits that were supposedly from observation.

There is, however, a criticism also to be leveled toward an observation-only approach to drawing. Namely, that while students may learn to see things and draw them more accurately through close observation, such drawings demonstrate only a superficial understanding of contours, shapes, values, and the like, and how they fit together to create the semblance of a thing. A student who is able to carefully observe and accurately draw a portrait might well notice the so-called waterline below the eye, but all it will be to that student is a subtly curving, narrow shape. At some point, the student may realize that it is in fact the thickness of the lower lid, that it is often bright because it is angled upwards toward the light, that it is evident on almost all people, and other characteristics beyond what are merely visible, but that will probably take time. Then again, the same student, in spite of his or her perceptual acuity, might still overlook (pun intended) the waterline and not include it in a drawing, because it is not a part of the student’s cognitive understanding of the eye.

I often discuss this problem with students, especially when teaching artistic anatomy, as a way of explaining why figurative artists must understand the bones and muscles of the body. Artists have long valued the study of skeletal and muscular anatomy because of one basic assumption: In order to draw the figure well, one must understand something of what is happening beneath the skin, so as not to draw the bumps and bulges on the body with slavish imitation, but with understanding. With understanding, it is argued, comes recognition, clarity, and—not least of all—more accurate drawing.

I often use the following analogy with students: If I go for a walk in the woods with Professor Skinner, an ornithologist, no matter how closely I pay attention during the walk, our experience will not be the same. Professor Skinner will recognize every bird that crosses our path, and know something about that bird’s habitat, range, migratory patterns, and so on. He will also recognize birds that don’t cross our path simply by hearing their calls. He may even hear certain calls that I don’t hear at all, because he is tuned in to these sounds and knows to listen for them. It is arguable whether Professor Skinner’s experience of the walk will be deeper or more profound than mine, but it certainly won’t be the same.

Nicolaïdes made a

similar analogy in The Natural Way to

Draw, using the example of a man from Mars trying to draw objects on the

earth. As Nicolaïdes described the situation, “we see through the eyes rather than with them….if you attempt to rely on

the eyes alone, they can sometimes actually mislead you.”7

Linear Perspective as an Example of Inventive Drawing Instruction

The point here, however, is not to argue whether drawing is better taught exclusively from observation or invention, but whether inventive drawing can play a positive role—along with observational drawing—in foundations instruction. In fact, with regard to certain topics, art instructors often demonstrate this to be true even in courses that are strongly observation based. One such topic that is frequently taught through both observational and inventive approaches is linear perspective. Though different instructors broach this concept in different ways, most instructors probably devote at least some time to the theoretical basis of perspective, with the necessary explanations of horizon line, vanishing points, and the like. Such theoretical instruction is, of course, instruction in inventive drawing (as with the example of the generic/theoretical eye). The student who learns this material can, with practice and diligence, go on to draw most any geometric object in depth, purely from the imagination.

Yet few drawing instructors, I presume, worry that such ability will lead the student to draw stereotyped still life objects. Rather, most art teachers probably find that teaching students the theory of linear perspective results in more accurate drawings of geometric objects, as students are able to use the theory to make sense of their perceptions—why they see more, less, or nothing at all of the tops of different objects; why certain edges appear to converge on each other and others do not; why some edges have very steep angles and others are flatter; and so on. In the same manner, learning something about the general appearance of eyes (and some of its common variations) enables students to make sense of their perceptions when drawing a portrait from observation, and learning to recognize the bones and muscles as they lie beneath a model’s skin enables students to draw a more convincing, naturalistic figure.

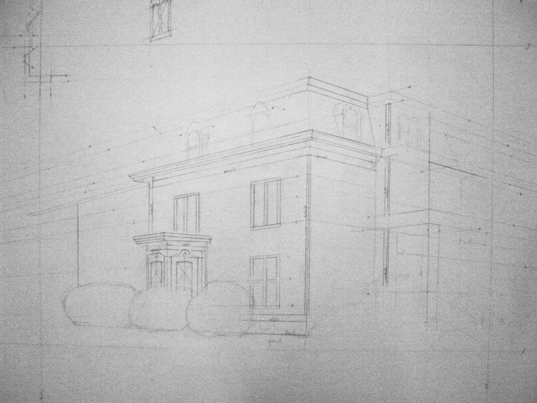

As an example of how understanding the theoretical basis of linear perspective can aid a student’s ability to draw geometric forms from observation, I will describe a typical situation involving architectural drawing. In an intermediate course that I teach, one observational assignment has the students draw some of the buildings on my college’s campus. Several of these buildings are converted Victorian-style homes constructed in the 1890’s. As with many older structures, certain features have settled over time, and parts that once were level or plumb are no more. A common situation is for students to be stymied by these features—they are able to accurately copy the angles of these forms through careful observation, sighting, and the like, but the result is a drawing that looks to be in flawed perspective.

Students who understand the principles of one- and two-point perspective, however, are usually able to identify where the building is structurally deficient, and to make an informed decision whether to correct their drawing accordingly. If they do choose to “restore” the building within their drawing, they might then proceed to find their eye level, draw out the orthogonal (perspective) lines in the drawing, and reconcile these lines with the appropriate vanishing points (fig. 4).

Implementing Inventive Drawing Instruction in Foundation Courses

The description of teaching linear perspective provides a useful example of how to implement inventive drawing instruction in courses. While acknowledging that methods for teaching perspective vary widely in college drawing courses, it is probably true that few instructors introduce the theory of perspective before students have tried drawing some geometric objects from observation. This is wise, and a good protocol to follow in general when introducing inventive practices into a curriculum.

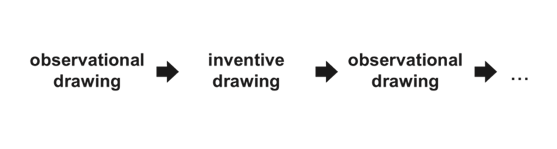

In short, such an approach follows the old dictum of “practice before theory.” With regard to educational theory, it follows what is variously called inductive teaching or indirect teaching, in which students first discover certain knowledge for themselves, before their discoveries are explained to them by an instructor. In terms of drawing instruction as I have described it in this paper, we can substitute the concept of observational drawing for “practice” and inventive drawing for “theory” (although, in the larger scheme of things, inventive drawing can be exceedingly practical).

An extension of this idea, and an even sounder approach for drawing instruction, is for students to return to some practical/observational application of their new skills after studying them in theory/inventively. Applying this approach to a curriculum that integrates inventive drawing instruction with observation-based instruction, the curricular model would look like that illustrated in fig. 6.

This cycle may be repeated as often as needed, or modified to allow for two or more observational assignments for every one inventive assignment, or vice versa. Alternating between observational and inventive assignments also dovetails nicely with class work versus homework assignments. Observational drawing works well in the classroom because of the availability of a live model in figure drawing classes, and because, in any drawing course, it allows all students to draw the same subject matter. Conversely, inventive drawing works well as homework because students “carry” their subject matter with them wherever they go.

An Example of Observational and Inventive Drawing Assignments

As a specific example of how an instructor might apply this curricular model to teaching basic drawing, let us examine a series of assignments that students might complete around the mid-point of a semester-long course. I will assume the students have learned something of contour drawing, sighting and measuring techniques, and linear perspective. Though it would not be true of all drawing courses, the next topic of study in this example will be that of shading or modeling objects under a source of directional light.

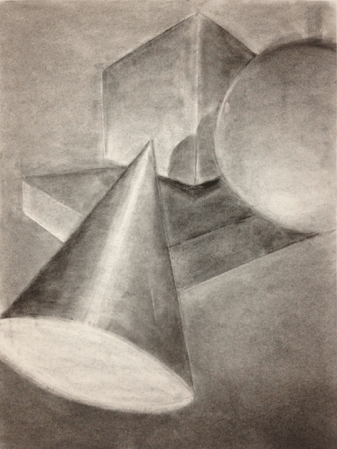

Because the students are versed in drawing from nature and understand some perspective theory, they are assigned a still life of white, geometric objects to draw from observation, shading the objects to match the values that they see. (Though specific details of the assignment are not crucial to this discussion, in my own course I introduce the technique of drawing on a medium-dark ground of charcoal, creating lighter values by erasing and darker values by building with charcoal. I find this to be a very user-friendly approach for learning to model objects under a light source.) The primary objectives of this assignment are 1) for students to draw the still life with accurate proportions, correct placement of objects in space, and a convincing sense of perspective; and 2) for students to match the values in their drawing accurately to the values in the still life, with attention to subtleties and nuance (fig. 7).

In keeping with an inductive approach to teaching, however, I provide little explanatory material regarding the new content of modeling objects in light and shadow. I do not, for instance, explain in advance of the assignment such phenomena as reflected light, though I usually do introduce such concepts as students naturally notice (or fail to notice) them during the course of the drawing. The only preliminary instruction I give for a drawing such as this is to demonstrate the use of any new media and techniques (the additive/subtractive technique described above). But regarding new conceptual ideas or visual phenomena, I prefer for students to discover such things on their own. Such self-discovery ensures a greater likelihood that the student will ascribe significance to the find, to say nothing of generating a greater level of excitement in the student.

Following completion of this drawing (or more than this one, if desired), I then introduce the problem of drawing a similar modeled still life from the imagination. To help the students with this, I may demonstrate, for instance, how the values on an object change depending on the orientation of a surface to the light source, what reflected light is and where it is likely to seen, how cast shadows differ from those dark values that are inherent to the form of an object, and what some of the particular characteristics of cast shadows are.

When I assign this drawing (typically as a homework assignment, fig. 8), I take advantage of the fact that it is an envisioned drawing and have the students arrange the objects as if floating in space, opposed to resting on a tabletop.8 This allowance complicates the drawing problem by allowing greater possibilities for composing the objects, in addition to increasing the difficulty of drawing them, as students are more likely to imagine floating objects as tilted or seen from below. The objects—about four to six of them—must be modeled as if under a light source coming from a single location, and shadows that one object might cast onto another must be taken into account. Because this is a challenging assignment, I usually have the students use the same medium and technique as in the previous, observed still life drawing.

Finally, the curricular model described previously would have the students return to an observational assignment following this inventive drawing. In my own course, I would introduce a new medium, technique, or concept at this point, though the crux of the new drawing problem would remain that of drawing geometric forms under a source of directed light. Most frequently, I introduce objects of different local values—white, gray, and black—with this assignment, whereas previously the students drew forms with only a single (light) local value.

Conclusion

The most challenging subject for inventive drawing, for both students and instructors, is undoubtedly the human figure. There are probably few fine arts figure drawing courses that devote significant time to the problem of drawing the envisioned figure in a naturalistic way. This is certainly less true of illustration courses, especially those that focus on sequential art and animation, but even in some of these courses the easy availability of photographic references and digital “posing” software lessens the need for artists to be able to draw the figure inventively.

Although the ability to draw a naturalistic figure from the imagination is not a mandatory skill for artists (including those who work figuratively), and though attainment of even rudimentary skill in this area is often a years-long process, some instruction in inventive figure drawing is beneficial in foundations drawing courses, for the reasons I have outlined in this paper. As is true of inventive drawing of other subjects, learning to draw the envisioned figure—even with marginal accuracy—serves the practical, long-term needs of a greater number of students in foundations drawing courses, and accelerates the attainment of skills for drawing the figure from observation.

There may be other

advantages, too, that inventive drawing offers for college art instruction than

those I have described here, but the immediate need is for more inclusion of

inventive drawing in foundations courses. In order for this to happen,

department chairs and foundations coordinators may need to accept a lower

standard of quality in inventive drawing assignments, and to be able to

identify these assignments as such. Instructors need encouragement to introduce

inventive assignments into their courses, without worry that the end result may

lessen the perceived effectiveness of their teaching. The process of education, especially at the foundations level, needs to

be emphasized over the product, and end-of-semester or end-of-year student

exhibitions should not be given undue prestige. Likewise, instructors need to

be confident in their own abilities to teach inventive drawing of a variety of

subjects, or to refresh their skills in these areas if needed. Finally, fine

arts programs need to relinquish any biases against inventive drawing

instruction. In this way, foundations drawing courses will be most effective in

teaching observational as well as inventive drawing, and in meeting the

professional needs of the greatest number of students.

Notes

- Kimon Nicolaïdes, The Natural Way to Draw: A Working Plan for Art Study (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1941).

- Bernard Chaet, The Art of Drawing (New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1978).

- Nathan Goldstein, The Art of Responsive Drawing (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1973).

- Betty Edwards, Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain (Los Angeles: J.P. Tarcher, 1979).

- Nicolaïdes, Natural Way to Draw, 9-10.

- Jack Hamm, Drawing the Head and Figure (New York: Perigree, 1963).

- Nicolaïdes, Natural Way to Draw, 6.

- I am indebted to the late Nathan Goldstein for this project, which he described in his excellent and now out-of-print textbook on painting. Nathan Goldstein, Painting: Visual and Technical Fundamentals Drawing (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1979).