Paper published in the Conference Proceedings of the 5th Annual Hawaii International Conference on Arts and Humanities. 2007. (ISSN# 1541-5899).

In considering a paper to present for this multidisciplinary conference on the arts and humanities, I could think of no topic more appropriate than the life and artwork of Dr. Ferdie Pacheco. Dr. Pacheco is famously known as a modern-day Renaissance man, for the Miami artist has been many things in his long and varied life: pharmacist and medical doctor, author of fourteen books on subjects ranging from fiction to art to Spanish cuisine, two-time Emmy award-winning documentary film producer, an internationally-recognized authority on the sport of boxing, boxing analyst and television executive, and, not least of all, a prolific and gifted painter.

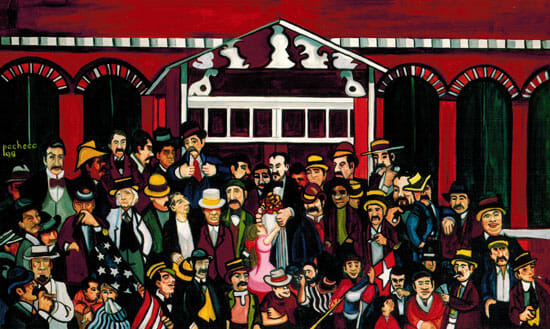

To the list of Pacheco’s demonstrable endeavors, we might also add one less evident pursuit: Pacheco as historian, if not in an academic sense, then as a keeper of stories and a chronicler of his own past. In his writings and artwork, especially the book Ybor City Chronicles and an ongoing series of paintings that focus on the immigrant community of Ybor City, Florida during the 1930s and 40s, Pacheco draws upon memories of his life and the lives of people he knew (or people he knew about; fig. 1). Perhaps it is more accurate to describe this pursuit as “aesthetic history,” researched and recalled through the interpretations of an artist. As Pacheco himself wrote in Ybor City Chronicles, “let me assure the reader that this book is not a history of Ybor City….These stories may not be the strict truth as other witnesses remember it, but they are the truth as I remember it. They are my truth.”1

In Pacheco’s paintings particularly, this focus on the remembered past is most intriguing, largely because of how unusual the subject is within that art form. In contrast to painting, such subject matter is not foreign at all to the literary arts; the memoir is a common genre in the field. But in painting, the “visual memoir” is rare, especially as an extended series of works (the closest parallel to a full-length book). The most notable example is Romare Bearden’s collage-paintings of his youth in North Carolina, Pittsburgh, and Harlem. We think also of Chagall’s reveries on the life of his Russian village, with the fantastic elements removed; Faith Ringgold’s tapestries of the African American experience; and the work of various folk and outsider artists, who have probably embraced the subject more than most mainstream artists. But with the exception of Bearden, none of them so thoroughly and rigorously chronicled the life of a specific time and place as Pacheco has done.

Though the term visual memoir is accurate, I think, in describing the pertinent works of these artists, it seems somehow inadequate in the context of the history of painting. Moreover, visual memoir has already gained some usage in a different context, typically describing photographic works of a documentary or nostalgic nature, especially when presented in book form. Perhaps the term memoir is just too closely associated with writing and with books (though the genre of the film memoir has gained wide acceptance under that name).

How, then, shall we describe this subject matter in painting? Genre painting comes close, I think, and it is tempting to think of artists such as Ferdie Pacheco as practitioners of this style, that is, as chroniclers of the specific and idiosyncratic activities of everyday life. But genre painters, at least in the conventional usage of that term, typically depict their own time and place. The high achievers of genre painting, the Dutch “little masters” of the seventeenth century—Vermeer, de Hooch, Terborch, Steen, and others—depicted the Holland of their day, and artists of lesser reputation who painted in the genre genre remained faithful to their locales, as well. In the case of Pacheco’s work, his subjects (excepting a few portraits) all reside in the past.

If genre painting does not accurately describe this subject then, we might reconsider Pacheco “the historian.” It is reasonable to think of Pacheco as a history painter, a recorder of days long gone, and of the people and places who occupied those times. But this also presents some difficulties, for history paintings, at least as academics use the term, are usually about more than just the past.2 Typically they depict grand or noble subjects, or subjects that are tragic but morally instructive. They celebrate the accomplishments of men and women whose names the viewer probably already knows, and whose deeds they might know, too. Although some of Pacheco’s works, such as a suite of U.S. Civil War paintings and the single painting Martí in Ybor City (fig. 2, depicting the Cuban revolutionary Jose Martí’s rally of the cigar workers in 1891), meet these criteria, the paintings that recall the artist’s own experiences lack the grandeur that is typical of most history paintings. Instead, these paintings recall the experience of the common individual—or even the displaced and downtrodden—so much so that Pacheco has referred to his work as a kind of “people’s art.”3

With regard to history painting, there is also a problem of stylistic incongruity with Pacheco’s manner of painting. Though issues of style are often superficial to the deeper meaning of artistic concepts or ideas, it is true that history paintings are typically rendered in a more-or-less naturalistic way, or in a way that is at least very different than the more primitive style of Pacheco’s work. Alberti himself, to whom the notion of history painting (istoria) is traditionally credited, considered the style of such work as inseparable from its content. The istoria, in Alberti’s judgment, was best realized in the form of illusionistic painting, the same illusionism he championed with his concept of a painting as a “window on the world.” The greater the illusion, the greater the istoria would impact the spirit and passions of the viewer. Though concepts such as Alberti’s istoria certainly evolve and expand over time, in Pacheco’s art we are stylistically a very long way from the masters of the quattrocento.

Perhaps the best description of Pacheco’s art, therefore, is a combination of the subjects his paintings don’t quite fit: that is, his art as genre history. This label, I think, would equally fit much of the work of artists such as Bearden, Ringgold, and others. But the lack heretofore of an appropriate term for this subject is only symptomatic of an underlying cause: namely, that the subject of genre history is not common in painting. The reasons why so many mainstream artists, both contemporary and throughout the ages, have ignored this subject, and why artists such as Pacheco and others have embraced it, are worthy of discussion.

It stands to reason that in painting one’s own past, that past should afford something of artistic interest, beyond whatever nostalgic appeal it might hold for the artist. We are all probably interested in our own past, but whether it provides the material necessary for artistic creation—or even the spark for artistic inspiration—is another issue. The sentiment that everyone’s life can be turned into art may be true on some level, but in practical terms (and especially with regard to the often narrative quality of genre history) some people’s pasts are simply more interesting than others’.

Though I do not think it necessary that this past be distant, it is true that time makes things less familiar, and the unfamiliar is often more intriguing, more mythic, and more poetically rich than the commonplace. The past, it is famously said, is a foreign country, and foreign lands entice those who would be travelers. Consequently, older artists are more likely to have a personal history that, at least in part, is potent for artistic exploration.

However, established artists are unlikely to begin looking at their own pasts as a subject for their art unless such subject matter relates in some way to the artist’s preexisting body of work. After all, artists who begin making art as young adults typically develop a mature style in the decade or two following their immersion in the field, and it is this style or “voice” (along with any subject matter they embrace) that often becomes the basis for their art for the remainder of their lives. Formal training methods, the example of other artists, and pressures from within the gallery world, among other things, all reinforce the need for artists to develop a distinct and recognizable imagery that may change little throughout the artist’s career. In this respect, the visual artist differs from the writer, who might navigate among different genres throughout a career, who might explore both fiction and nonfiction writing during that time, and who can write the autobiographical memoir without it seeming incompatible with the rest of his or her oeuvre.

This may explain why genre history is more common as a subject in the work of untrained artists, who often do not begin making art until later in their lives. At that point in life, their personal history may offer much for their artwork to explore, and the art is not yet tied to any preexisting imagery or ideas.

Certainly this was the case with Ferdie Pacheco. Though his interest in the visual arts goes back to his childhood, and though he drew cartoons and sketched regularly through his adult years, he did not begin to seriously paint until his mid-50s. Pacheco’s immersion in painting followed a highly successful career running clinics in Miami and, most famously, his role as personal physician and fight doctor for Muhammad Ali. The fact that his life at that point had not only been reasonably long but had been one of incredible richness and opportunity provided ample material for his art, and from a very early stage his paintings were largely autobiographical. The first Ybor City paintings began in the mid-1980’s, with the subject reaching maturity over the next decade. The series continues to the present day.

The evolution of these paintings coincided with Pacheco’s literary explorations into his own past and the history of Ybor City, as recorded in the autobiography Fight Doctor (1977) and the book Ybor City Chronicles (1994). Whether or to what degree Pacheco’s autobiographical writings influenced the choice of subject matter for his paintings (or whether the paintings influenced the books) is uncertain; the artist has not acknowledged a connection either way. It is true that Fight Doctor preceded the Ybor City paintings by several years, but that book focused on Pacheco’s “boxing career,” not his youth in Florida. It is possible, however, that in writing that first memoir (he has written at least three) the idea was planted that art in any form—written, visual, or otherwise—can involve the past and one’s memories of it.

That Pacheco turned to painting later in life explains many of his views about art. “The artist is a distillation of all he has lived, been taught, seen, and all that has affected him in his lifetime.”4 Though undeniable, it is the kind of statement that only an artist with a great life to draw on could say without depreciating oneself and one’s art. And while Pacheco the artist may be a distillation of his life and experiences, his paintings are not a distillation but rather an amplification of that same life and of that genre history.

Notes

- Ferdie Pacheco, Ybor City Chronicles (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1994), ix.

- For a useful discussion of history painting, see Vernon Hyde Minor, Art History’s History 2d ed. (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2001), 60-65.

- Ferdie Pacheco, Pacheco’s Art of Ybor City (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1997), xviii.

- Ibid., xix.